Aggregators or two-sided marketplaces are a profitable business model. There are a lot of startup pitches that start with ‘we are building Uber for x or Airbnb for y’. There is no doubt that aggregators can become incredibly valuable, profitable, and powerful. However, building an aggregator is not easy. Understanding how aggregators work and what it takes to build a successful aggregator is essential.

Before digging deeper, we start with breaking down what are the competitive advantages of aggregators by examining the aggregation theory. In 2015, Ben Thomson defined aggregation theory as follows:

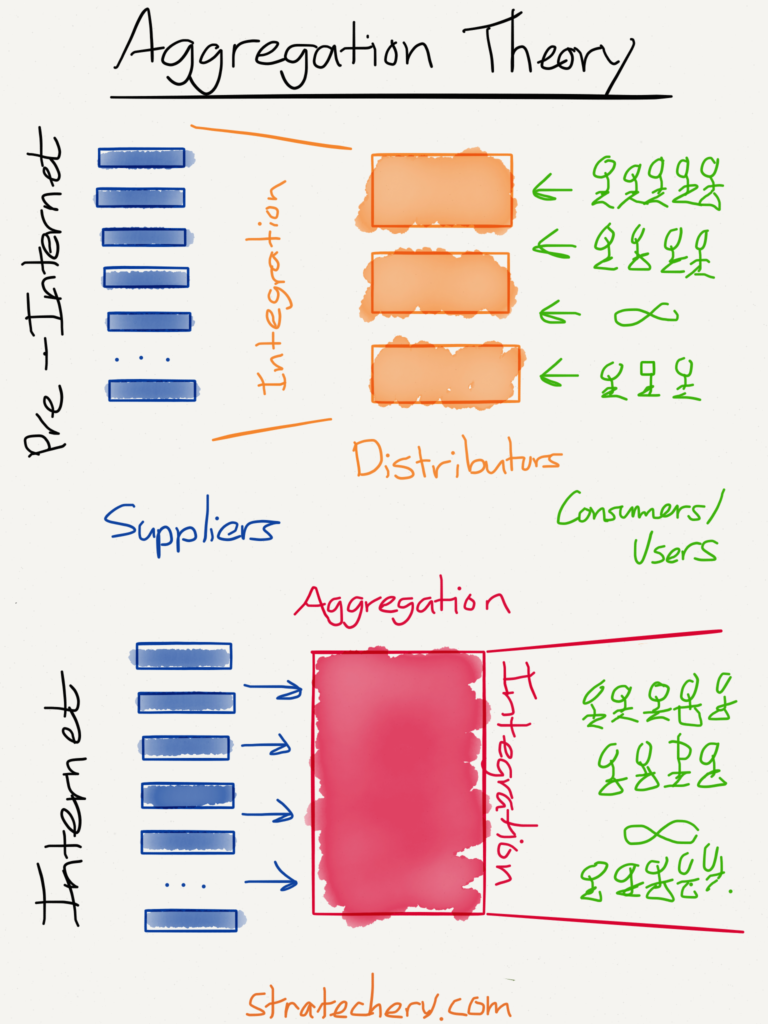

The value chain for any given consumer market is divided into three parts: suppliers, distributors, and consumers/users. The best way to make outsize profits in any of these markets is to either gain a horizontal monopoly in one of the three parts or to integrate two of the parts such that you have a competitive advantage in delivering a vertical solution. […]

The fundamental disruption of the Internet has been to turn this dynamic on its head. First, the Internet has made distribution (of digital goods) free, neutralizing the advantage that pre-Internet distributors leveraged to integrate with suppliers. Secondly, the Internet has made transaction costs zero, making it viable for a distributor to integrate forward with end users/consumers at scale.

This has fundamentally changed the plane of competition: no longer do distributors compete based upon exclusive supplier relationships, with consumers/users an afterthought. Instead, suppliers can be aggregated at scale leaving consumers/users as a first order priority. By extension, this means that the most important factor determining success is the user experience: the best distributors/aggregators/market-makers win by providing the best experience, which earns them the most consumers/users, which attracts the most suppliers, which enhances the user experience in a virtuous cycle.

By this definition, a considerable number of today’s prominent technology companies can be classified as aggregators. They became very successful by automating distribution, and instead of aggregating suppliers, focused directly on providing the best end-user experience. Here are a few examples:

- Facebook: Aggregating content from users’ friends and advertisements and making them available to other users;

- Airbnb: Aggregating vacant rooms globally and providing an interface for consumers;

- MoneySuperMarket.com: Aggregating UK insurance products and selling them to UK consumers;

- AutoTrader: Aggregating UK car sales listings for UK consumers; and

- Google: Aggregating free content from the web and making it searchable for consumers.

Aggregation theory explains how successful tech giants think. It also serves as a warning to industries who are still based on controlling distribution. There are three key types of aggregators. Each type is determined by the cost/effort of scaling supply and demand and cadence of usage by consumers. Let’s look at a few examples to make it clear.

Micro Aggregators

Micro aggregators must spend a significant amount of time and money to integrate different suppliers into their platform and have excessive costs attracting customers. Often, they must build a relationship with each individual supplier and integrate them into the platform. Moreover, the integration effort is not repeatable for other suppliers, and each supplier requires its own integration effort.

A good example of this kind of aggregator is MoneySuperMarket.com or comparethemarket.com, which are insurance comparison sites. They must build a relationship with every insurance provider and integrate them individually to their platform. Integrating a new insurance provider requires the same amount of integration work.

Scaling demand is also not cheap for these kinds of aggregators. Due to the fierce competition in the space and the lack of differentiation, these firms have a very high cost of customer acquisition. For example, UK price comparison websites spend £48 on average to get a consumer to their website. The other important dynamic of these aggregators is how often people use them. For example, for UK price comparison websites, this is only a few times a year.

Still, these aggregators can be very profitable and very successful. However, there is a limit to how much they can grow. Apart from the above points, another growth limitation factor is legislation. For these aggregators to enter a new market (usually a new country), they need to adhere to new rules and regulations and build new relationships with new suppliers.

Global Aggregators

Global aggregators incur significantly less costs when bringing on new suppliers to their platform; however, they still have high customer acquisition costs. The process of bringing on new suppliers is repeatable. Uber and Airbnb are examples of global aggregators. Once the platform is up and running, the cost of adding a new driver or a new house or even a new city is not much when compared to the cost of building the platform.

The cost of acquiring customers is still noticeable; however, these customers come back to these platforms multiple times a year, and in the case of Uber, multiple times a week. As we can see with Uber and Airbnb, these aggregators can be global dominators.

Super Aggregators

Super aggregators do not incur any costs to obtain suppliers and consumers. Google, Facebook, and Instagram are examples of super aggregators. In the case of Google, their supply is web content and advertisements. Web content is freely available to everyone, and they have an automated and scalable process for onboarding advertisers to their platform. Facebook’s supply comes for free from our photos, videos, status updates, and content that we share from the media. They use the same strategy as Google for scaling advertisers on their platform.

Super aggregators have zero customer acquisition costs, as they are highly differentiated and have monopolies in what they do. With consumers often using these platforms multiple times a day, there is almost no limit on how big supper aggregators can become, and that is why Facebook and Google are two of the most valuable companies in the world.

Market valuation of aggregators is a function of the cost of customer acquisition and supplier integration.

The Internet takes away the cost of distribution. Essentially, everyone can become their own distributor by putting up a website or a mobile app and reaching out to end users. However, in an increasingly fragmented web ecosystem, discoverability becomes a big problem.

This is why aggregators can be very profitable and valuable. They do not create goods, services, or content. However, they provide the best user experience for consumers to discover and use goods, services, or content. To that end, suppliers have no choice but to partner with these aggregators for distribution.